Growth for Startups

A comprehensive guide to startup growth covering product-market fit measurement, growth channels, conversion optimization, and data-driven decision making through A/B testing.

Most startups fail because they misunderstand growth. They launch their product and expect users to magically appear. But the world doesn't work that way. No one is waiting for your product to launch. No one cares about your startup until you make them care.

This is the reality that founders need to accept early on. Growth doesn't happen automatically—it's something you have to engineer, often through methods that feel unnatural or even embarrassing to someone coming from a corporate background.

The Myth of "If You Build It, They Will Come"

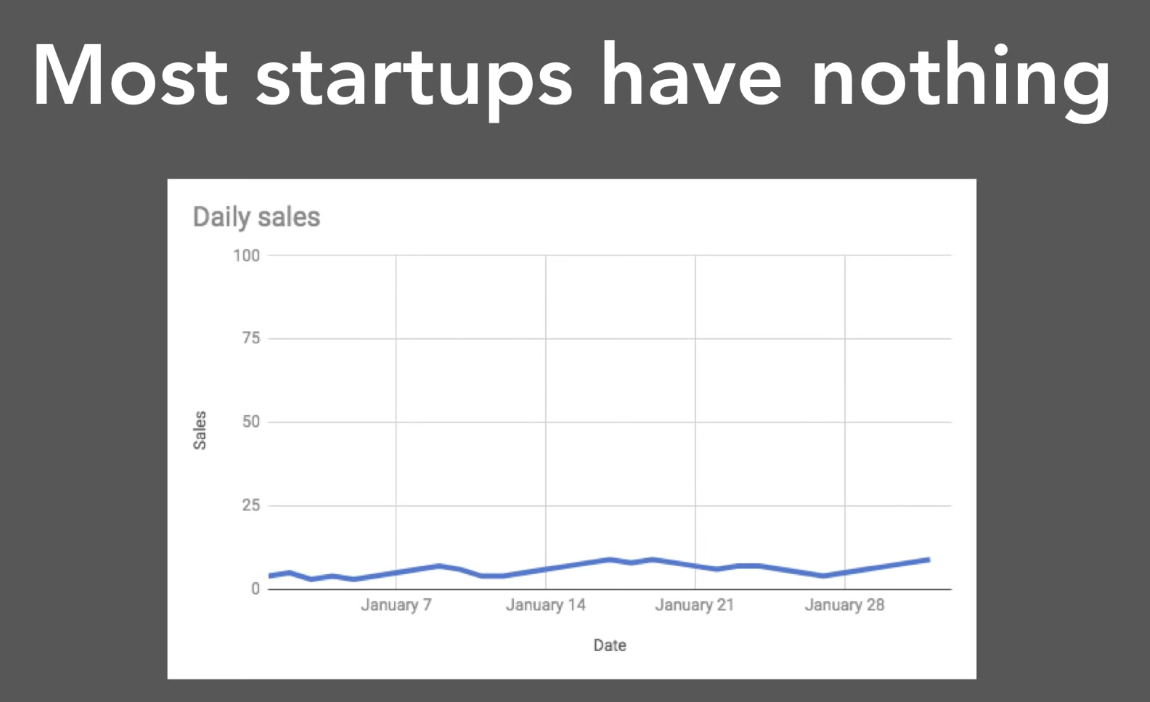

Most startups don't have product-market fit, despite what their founders believe. The founders convince themselves their product is working, but the data tells a different story. And most people still believe the old adage "if you build it, they will come." But the reality is: if you build it, they won't come.

The world is a busy place. People aren't standing around waiting for your product to launch. They're not going to discover it organically. This comes as a shock to many founders, especially those coming from big companies where distribution wasn't their problem.

When you launch a startup, everything is on you. There's no marketing department, no sales team, no brand recognition. You have to figure out how to reach people who don't know you exist.

Doing Things That Don't Scale

The solution is to do things that don't scale. This concept comes from Paul Graham's foundational essay, and it's the core philosophy that drives early-stage growth at Y Combinator.

When you're just starting out, you need to manually recruit, onboard, and delight users before trying to automate or scale. This means doing things that feel unnatural—things you didn't learn in business school or at your previous job.

Take Airbnb's early days. The founders would fly to New York, meet with hosts in person, take professional photos of their listings, and fix bugs on the spot. They weren't the founders when they met hosts—they claimed to be hired photographers for "AirBed & Breakfast." This made the company sound bigger than it was.

While one founder took photos, the other would sit down with the host and ask questions: "What challenges are you having with the product? What's not working? Can you show me how you use the product?"

They learned things they never could have discovered sitting in front of a computer. The payout system didn't work. There were UI bugs on certain pages. The site didn't work well on Internet Explorer.

The next morning, they'd send an email: "Here are all the photos we took of your house, now up on AirBedAndBreakfast.com. By the way, we fixed half the bugs you mentioned yesterday."

This made the hosts love them. These hosts became the backbone of Airbnb's early growth.

The lesson is clear: founders are the ones who make startups take off. You have to do unconventional things. You have to do things that don't feel right. You have to do things you didn't learn in business school.

Measuring Product-Market Fit

Once you've started doing things that don't scale, you need to measure whether you're actually building something people want. This is where most founders go wrong—they rely on the wrong metrics.

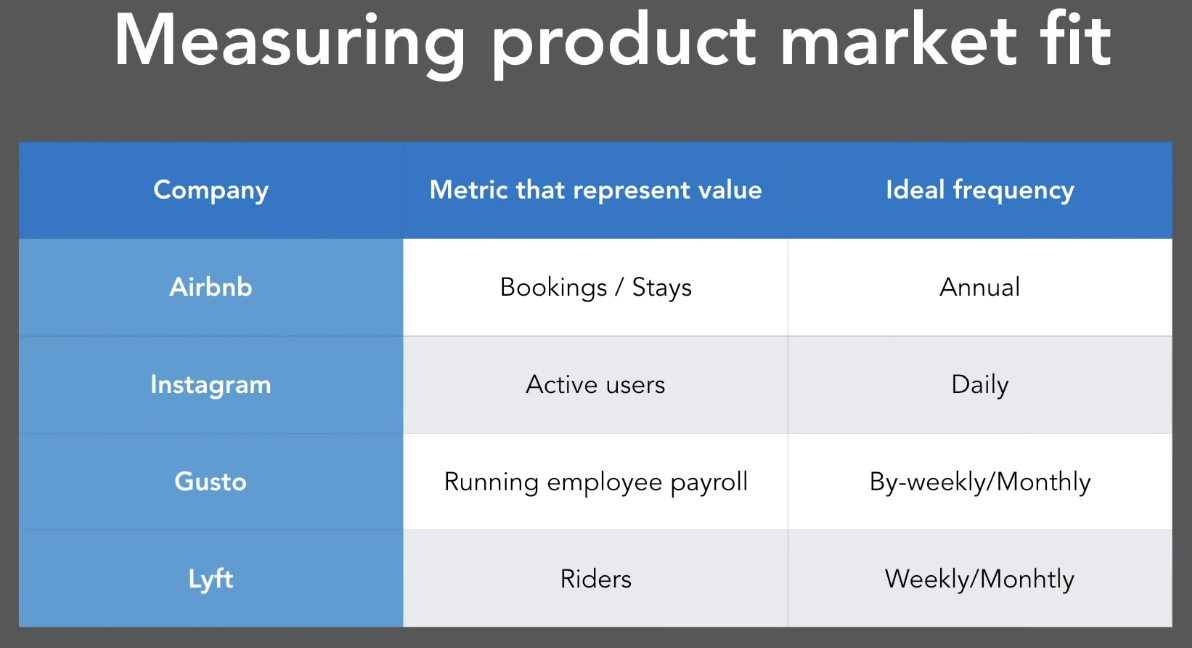

The best way to measure product-market fit is through retention data. Specifically, you need to identify two things:

- The metric that represents the value your users get from your product

- How often users should reasonably engage with that metric

For Airbnb, the value metric is bookings and stays (not searches). For Instagram, it's returning to view photos (not posting daily). For a B2B company like Gusto, it's running payroll (probably bi-weekly or monthly).

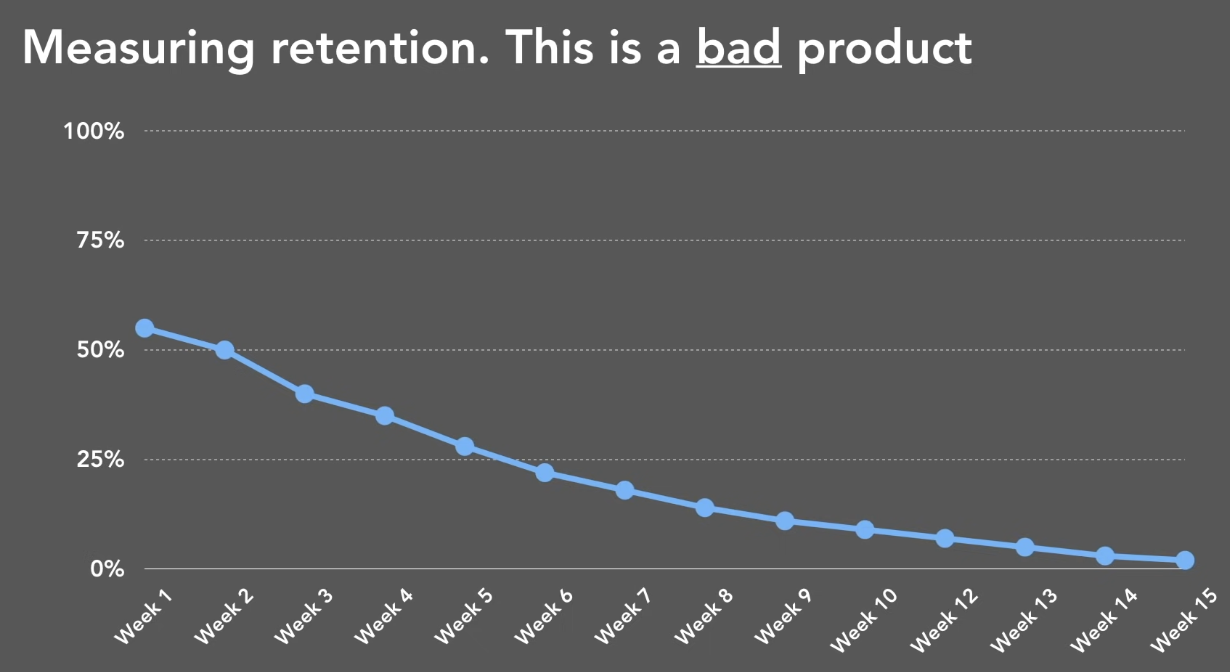

Once you have these two metrics, you can plot retention curves. Week 0: you have 100 users. Week 1: how many of those users are still using your product? Week 2, Week 3, and so on.

Repeat usage is the most unbiased way to figure out if someone likes your product. It's more reliable than what they tell you. People might say they love your product, but what they do is what matters.

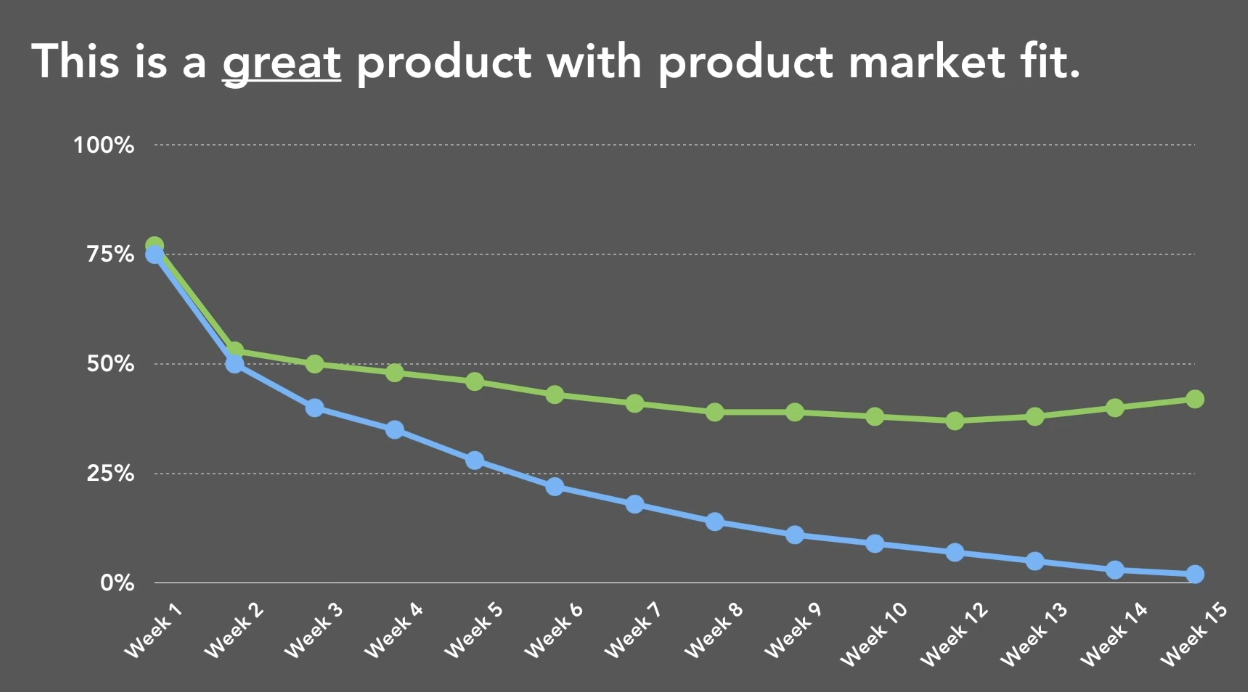

A bad product shows a retention curve that drops every week. Fewer and fewer people continue to use it. But a good product eventually flattens out. The people who stop using it stop, and you're left with a core group that continues to use it every week.

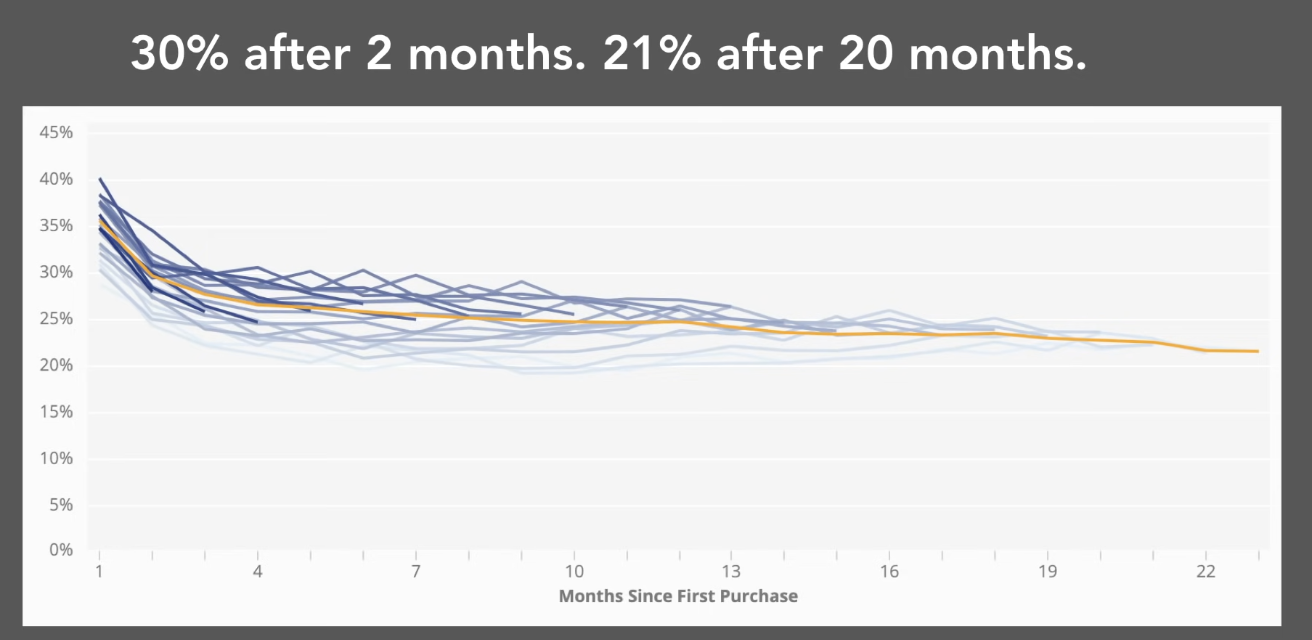

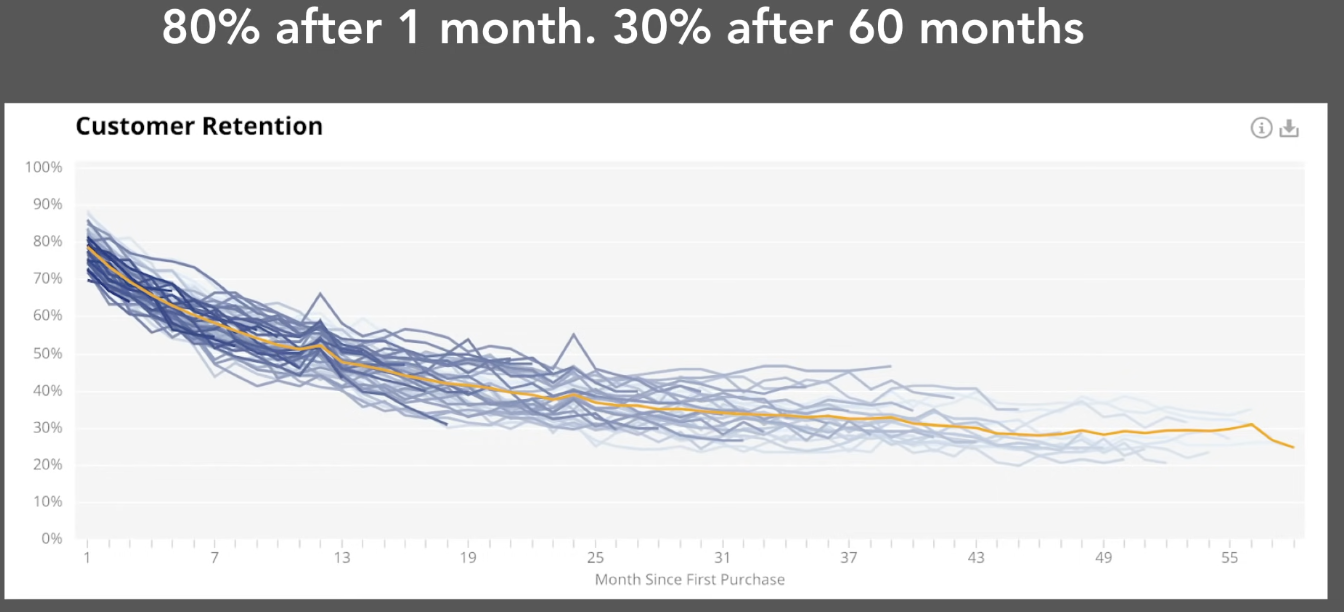

Some companies that have achieved product-market fit: DoorDash has 30% retention after two months and 21% after twenty months. GitHub has 80% retention after one month and 30% after 60 months.

What Not to Measure

There are several metrics that people think indicate product-market fit but don't:

Net Promoter Score - Not reliable. Some of the best products in the world have bad NPS scores.

Surveys - Often biased. Users tell you what they think you want to hear.

"How would you feel if you couldn't use this product?" - Sometimes works, but not as reliable as retention data.

Bad metrics to avoid:

- Registered users (doesn't say anything about repeat usage)

- Visitors (doesn't indicate if your product is valuable)

- Conversion rate (doesn't tell you who you're converting)

- Free users for a paid product (if people won't pay, they don't really value it)

Growth Channels and Tactics

This section only applies if you have product-market fit. If most people who try your product never come back, don't work on growth channels. Focus on fixing your product first.

There are two main ways to grow at scale:

1. Product Growth / Conversion Rate Optimization

This means engineers, designers, and product managers working on improving specific parts of your product to get more people through your funnel.

Every product is a funnel. Take Airbnb: Homepage (P1) → Search Results (P2) → Listing Page (P3) → Booking Page (P4). Your job is to figure out what percentage of people make it from P1 to P4, why they're dropping off, and how to increase that number.

Every step in the funnel has drop-offs. People might leave because the content doesn't speak to them, the site doesn't work on their browser, or any number of other reasons.

Common areas for conversion optimization:

- Internationalization - Translating your product

- Authentication - Making sign-up flows work perfectly

- Onboarding - Making the experience better for new users

- Purchase conversion - Optimizing the buying process

2. Growth Channels

These are platforms where people discover products: Google, Facebook, Instagram, etc.

Most companies grow huge using only 1 or 2 of these channels. You don't need to master all of them.

When to use each channel:

- Google/SEO - If your product is a rare behavior (like finding insurance or a doctor)

- Referrals & Virality - If users already share your product through word of mouth

- Social Networks - If your product gets better with more users (like LinkedIn or Airbnb)

- Sales - If you can make a list of your customers (B2B companies)

- Paid Advertising - Only if you have revenue and people are paying for your product

Referrals and Virality

Referrals are engineered word of mouth. If word of mouth is a strong driver of your product, referrals can amplify it.

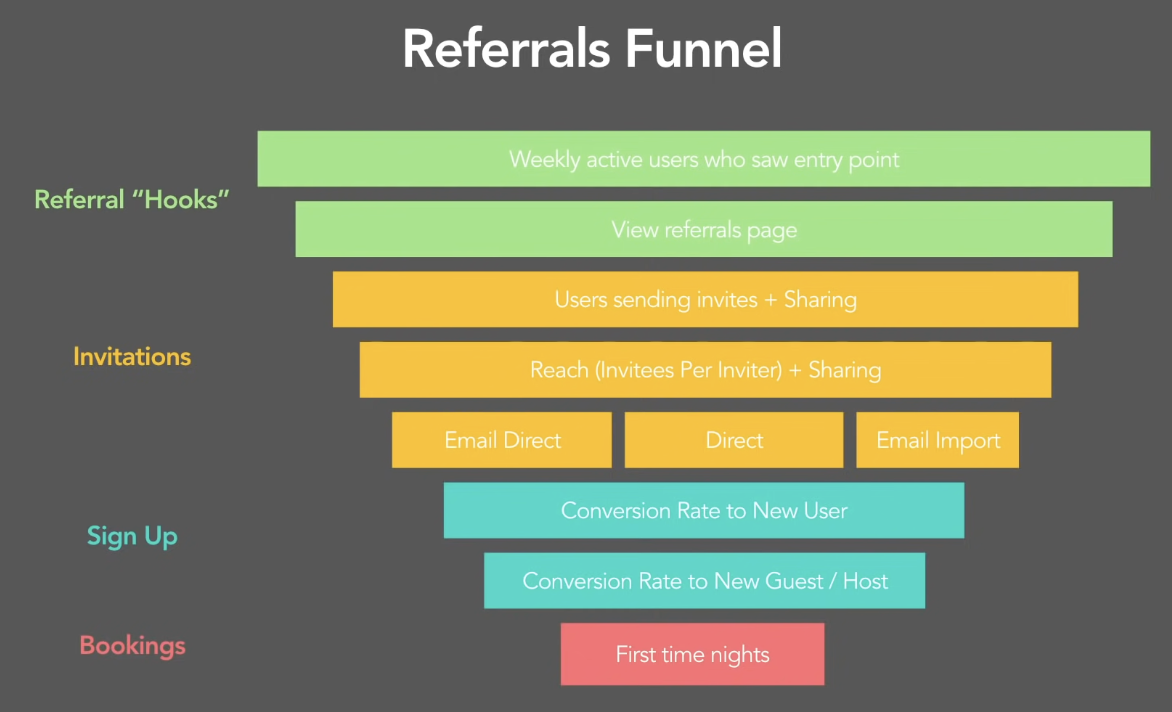

Airbnb's referral program is simple: give someone $40 to sign up, and when they do, you get $20. But the implementation is complex. You need to measure each step in the funnel: how many people see the offer, how many send invites, how many clicks, how many sign-ups, how many book.

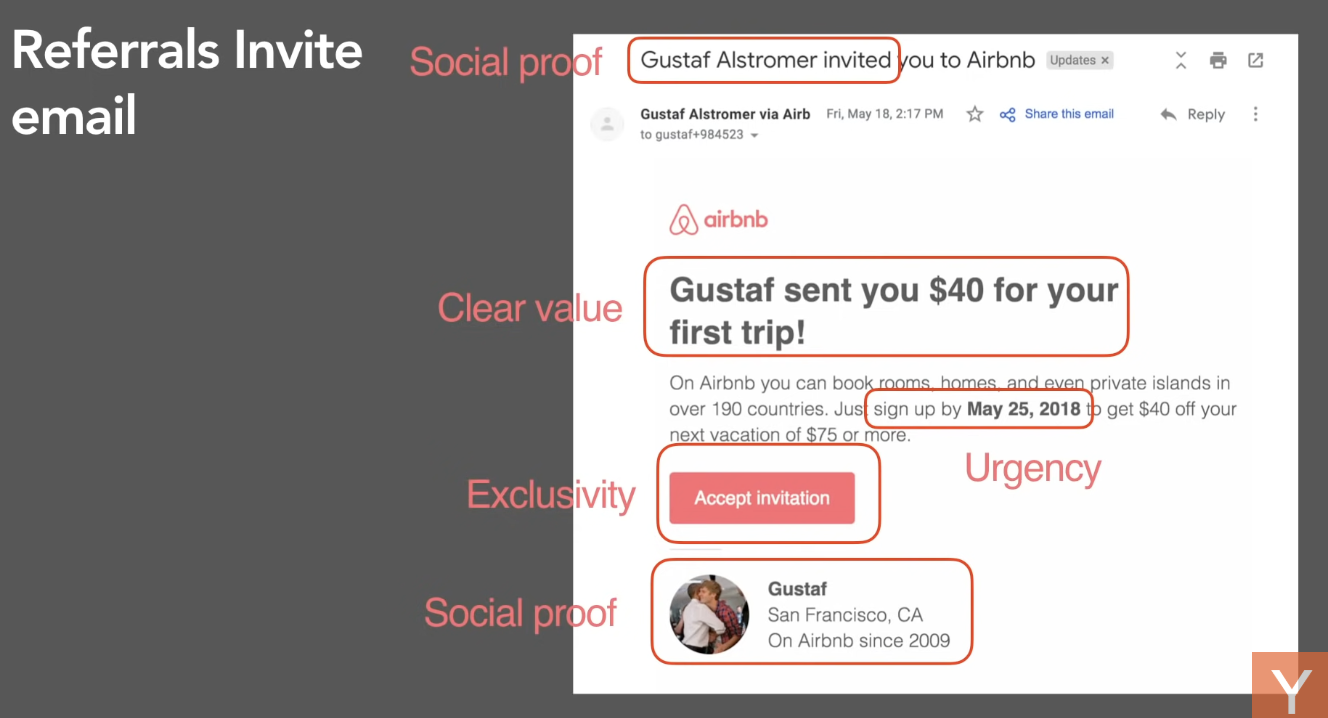

The referral email is critical. Optimize the sender (personal vs. company), clear value proposition, urgency, call-to-action, and social proof.

Paid Growth

The number one rule: don't do paid growth unless you have revenue. This is the most common mistake founders make.

You need to understand your Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) and ensure your predicted revenue is higher than the CAC. Most advertising tools will tell you the cost once you start running ads.

The main channels are Google, Facebook, and Instagram. That's pretty much it.

SEO

SEO has become very competitive. Big companies like Pinterest and TripAdvisor now rank for every keyword in their space. To compete, you need to be as good as they are.

SEO has two main levers:

-

On-page optimization - Start with keyword research. What are people searching for? Build content around those keywords.

-

Off-page optimization - Domain authority and inbound links. The more high-authority sites link to you, the more valuable Google considers your site.

Making Decisions with A/B Testing

Most early-stage startups don't need A/B testing. But when you get bigger and have multiple people making decisions, it becomes essential.

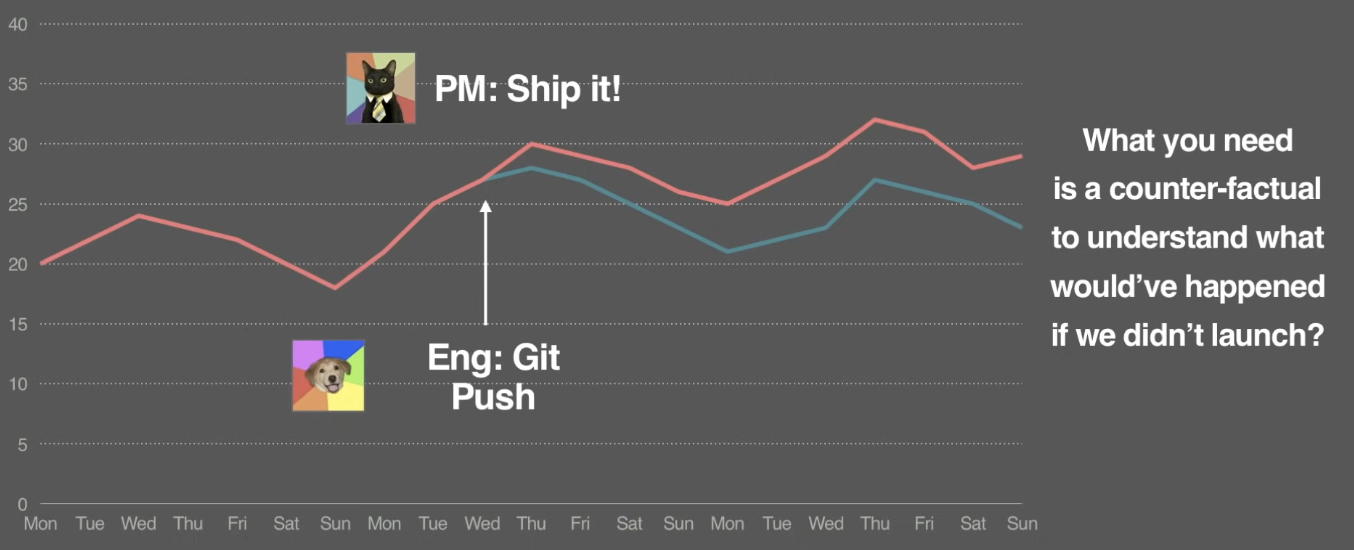

The problem: you launch a new design, and your metrics go down. What happened? You don't know if it was the design or something else.

A/B testing creates two parallel universes—one with your change, one without. You can then measure exactly what impact your change had.

At Airbnb, they tested a new sharing sheet for mobile. The old version used the native iOS share sheet. The new version showed more options but didn't look native. Which was better?

They ran an A/B test. The new version was 40% better. Without the test, they would have made the wrong decision.

Another example: sign-up walls in the app. Should users be able to use the app without signing up, or should there be a wall they can't skip?

The sign-up wall resulted in 2.6x more bookings. Why? They could show more personalized content and users didn't have to sign up at booking time.

Summary

-

Start by doing things that don't scale - Unlearn what you learned in business school. Do manual, personal work to get your first users.

-

Measure your retention - Use data to understand if you have product-market fit. Retention is the most reliable indicator.

-

Build a culture of experimentation - Use data and A/B testing to make decisions, not the loudest voice in the room.

Most of you reading this won't need to worry about advanced growth tactics yet. Focus on the basics: getting your first users, measuring retention, and building something people actually want. The rest will come later.

The key insight is that growth is not automatic. It's something you have to engineer, often through methods that feel unnatural. But it's the only way to build a successful startup.

Notes

[1] The concept of "doing things that don't scale" comes from Paul Graham's foundational essay. It's a core YC philosophy for early-stage growth: manually recruit, onboard, and delight users before trying to automate or scale.

[2] The cautionary reminder that "most startups think they have product-market fit but don't" echoes advice from YC partners like Michael Seibel and Dalton Caldwell, who emphasize measuring user behavior over relying on surveys or NPS.

[3] The retention curve visualizations and PMF measurement tactics are drawn from YC startup school curriculum and talks by experts like Gustaf Alströmer. They emphasize usage-based metrics as the gold standard for PMF.

[4] The distinction between product growth and growth channels, as well as funnel examples (like Airbnb), are based on real-world scaling experiences from YC-backed startups and internal product teams.

[5] The advice to avoid paid marketing until you have revenue and a proven product comes from countless YC office hour sessions and case studies. Many startups fail by prematurely optimizing CAC before they know LTV.

[6] A/B testing and experimentation practices outlined here are influenced by growth leaders at companies like Airbnb, Dropbox, and Pinterest. YC generally advises early-stage founders not to start A/B testing too soon—until traffic, data volume, and product stability justify it.